The Idolatry of Bible Worship

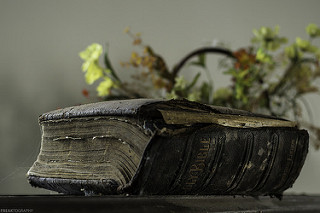

[Know that I do not mean to inspect the idolatry within the Bible, but speak of the sola scriptura within the five solae (others being sola fide, sola gratia, solus Christus, and soli Deo gloria). Photo by Freaktography]

The Church is ossified. I believe that the mass exodus from the church in our contemporary western world is due to this scaling over of the eyes of the Church. Is it not a bony, skeletal, stiff thing compared to its bright cousin, the Spirit Church? And so this is what I label as the Church's successor: the spirit church, the church which casts off the stiff structure of doctrinal worship (ie, worship of doctrine) and replaces this with an experiential, spiritual commune of those willing to put Christ's passion for us over all other things. Over even the Bible, which seems to be the last object left to the Church, the last relic which it clings to with long, sharpened, clinging claws.

But I do not cast the Bible out entirely--only the worship of the Bible. And make no mistake: the fundamentalist churches do worship the Bible. They claim it inerrant, despite the asymmetry between different versions (Sinai Bible vs others), despite the obvious textual problems (contradictions, later insertions, stylistic asymmetries). They claim its literalness, despite language's inherent sloughing off of literality (language is not mathematics). They claim its "divine inspiration," while discounting the "divine" inspiration of other art forms (why cannot Shakespeare and Chaucer and Cervantes be considered divinely inspired through their genius? And that is only within the literal arts. What of Raphael? Goya? What of Balanchine? Bach?)

The fundamentalist understanding of the Bible is constricted, small-minded, and wrong. If they wished--they decidedly do not--to expand their understanding of the Bible they would peer into translation theory, and broaden their scope with the understanding of comparative literature.

Giambattista Vico, an Italian philosopher of the 18th C., asserted that people understand the lowly and the humble, not the highest reaches of heaven. That we relate to the real world treatments of literature, not the high-born depictions of the gods. We understand humanity, not God. [cf Echevaria's "Cervantes' Don Quixote" pp 202-203.] A Bible class that treats the Bible as inviolate word of God, forever to be separated from the mind of man by some superstitious treatment of the book as Holy Word instead of an example of men attempting some mythic understanding of God's place in their world, worthy of high praise but also worthy of the honest appraisal of its failure--as any treatment of God is doomed to fail within literature. (As an aside, I think Hafiz' poem "Someone Should Start Laughing" contains at least some effort to understand the weakness of language when confronted with the divine: "If you think that the Truth can be known/from words/If you think that the sun and the ocean/can pass through that tiny opening/called the mouth/Oh someone should start laughing.")

What the fundamentalists do is take the high-minded fantastical Bible (who could say it was not fantastical? Noah and the Ark? Moses' and the 40-year trek along with the dividing of the Red Sea? The Virgin Birth?) and coat it with such gilding that it lacks approachability, all understanding, setting it up for the only thing left for it: indoctrination. Dogma comes from our attempt to bring the inapproachable into our hearts.

I think the figures of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza are instructive here. Our effort to assimilate the heavenly, the fantastical --the fantasy-- can be compared to Don Quixote's madness. We cannot understand his world of chivalry and romance. It has no comparison to our real world. The real world of our experience is more like Sancho Panza, with his concentration on eating and real-world concerns. Don Quixote's preoccupation with fantasy has value--there is beauty there and morality of a kind--as does Sancho's world, the world that we all really live in. But it is when we combine them that we get to the real point. That the real world of everyday, the world of experience, when overlaid with the fantasy of the heavenly (which is not approachable or understandable by us), is our path to a spiritual understanding.

We cannot treat Don Q. like God. That is madness. But that is what we do when we make the Bible our God (is that not what we do when we treat the Bible as the very inerrant Word...In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The Word equated with Christ.

The Word--Christ--is more Sancho than Quixote, more humble than lofty, more of society than heavenly kingdom. The following of a madman (Don Q) leaves us thirsty for more, like Sancho found himself, but it leads us into an unknowable cave, a dream, like the Cave of Montesino.

So where is the real Bible, the real Word of God? It must be found where Christ found it, in the "kingdom of heaven" of the woman making her dough, of the family with the new-found prodigal son, found among us, experiencing the real world. It is not so much Sancho Panza as our new Bible, as both Sancho and the Don experiencing life together, the highs and the lows, the fantastical imaginings of art along with the everyday happenings around us coalescing into a new experience, a new birth of a spiritual awakening, something that will never happen with us dreamily contemplating the madness of a false god.

The Bible is a pointer, a sign that tells us where we can find Truth, where we can start a journey to God. It is not that path itself, a path we guild with gold and dare not step on for defiling God himself. We should walk on it, study it, use it. But do not idolize it. That is madness, no better than Don Quixote's infatuation with romance.

The Church is ossified. I believe that the mass exodus from the church in our contemporary western world is due to this scaling over of the eyes of the Church. Is it not a bony, skeletal, stiff thing compared to its bright cousin, the Spirit Church? And so this is what I label as the Church's successor: the spirit church, the church which casts off the stiff structure of doctrinal worship (ie, worship of doctrine) and replaces this with an experiential, spiritual commune of those willing to put Christ's passion for us over all other things. Over even the Bible, which seems to be the last object left to the Church, the last relic which it clings to with long, sharpened, clinging claws.

But I do not cast the Bible out entirely--only the worship of the Bible. And make no mistake: the fundamentalist churches do worship the Bible. They claim it inerrant, despite the asymmetry between different versions (Sinai Bible vs others), despite the obvious textual problems (contradictions, later insertions, stylistic asymmetries). They claim its literalness, despite language's inherent sloughing off of literality (language is not mathematics). They claim its "divine inspiration," while discounting the "divine" inspiration of other art forms (why cannot Shakespeare and Chaucer and Cervantes be considered divinely inspired through their genius? And that is only within the literal arts. What of Raphael? Goya? What of Balanchine? Bach?)

The fundamentalist understanding of the Bible is constricted, small-minded, and wrong. If they wished--they decidedly do not--to expand their understanding of the Bible they would peer into translation theory, and broaden their scope with the understanding of comparative literature.

Giambattista Vico, an Italian philosopher of the 18th C., asserted that people understand the lowly and the humble, not the highest reaches of heaven. That we relate to the real world treatments of literature, not the high-born depictions of the gods. We understand humanity, not God. [cf Echevaria's "Cervantes' Don Quixote" pp 202-203.] A Bible class that treats the Bible as inviolate word of God, forever to be separated from the mind of man by some superstitious treatment of the book as Holy Word instead of an example of men attempting some mythic understanding of God's place in their world, worthy of high praise but also worthy of the honest appraisal of its failure--as any treatment of God is doomed to fail within literature. (As an aside, I think Hafiz' poem "Someone Should Start Laughing" contains at least some effort to understand the weakness of language when confronted with the divine: "If you think that the Truth can be known/from words/If you think that the sun and the ocean/can pass through that tiny opening/called the mouth/Oh someone should start laughing.")

What the fundamentalists do is take the high-minded fantastical Bible (who could say it was not fantastical? Noah and the Ark? Moses' and the 40-year trek along with the dividing of the Red Sea? The Virgin Birth?) and coat it with such gilding that it lacks approachability, all understanding, setting it up for the only thing left for it: indoctrination. Dogma comes from our attempt to bring the inapproachable into our hearts.

I think the figures of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza are instructive here. Our effort to assimilate the heavenly, the fantastical --the fantasy-- can be compared to Don Quixote's madness. We cannot understand his world of chivalry and romance. It has no comparison to our real world. The real world of our experience is more like Sancho Panza, with his concentration on eating and real-world concerns. Don Quixote's preoccupation with fantasy has value--there is beauty there and morality of a kind--as does Sancho's world, the world that we all really live in. But it is when we combine them that we get to the real point. That the real world of everyday, the world of experience, when overlaid with the fantasy of the heavenly (which is not approachable or understandable by us), is our path to a spiritual understanding.

We cannot treat Don Q. like God. That is madness. But that is what we do when we make the Bible our God (is that not what we do when we treat the Bible as the very inerrant Word...In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The Word equated with Christ.

The Word--Christ--is more Sancho than Quixote, more humble than lofty, more of society than heavenly kingdom. The following of a madman (Don Q) leaves us thirsty for more, like Sancho found himself, but it leads us into an unknowable cave, a dream, like the Cave of Montesino.

So where is the real Bible, the real Word of God? It must be found where Christ found it, in the "kingdom of heaven" of the woman making her dough, of the family with the new-found prodigal son, found among us, experiencing the real world. It is not so much Sancho Panza as our new Bible, as both Sancho and the Don experiencing life together, the highs and the lows, the fantastical imaginings of art along with the everyday happenings around us coalescing into a new experience, a new birth of a spiritual awakening, something that will never happen with us dreamily contemplating the madness of a false god.

The Bible is a pointer, a sign that tells us where we can find Truth, where we can start a journey to God. It is not that path itself, a path we guild with gold and dare not step on for defiling God himself. We should walk on it, study it, use it. But do not idolize it. That is madness, no better than Don Quixote's infatuation with romance.

Comments